Preserving Kathleen Collins' Legacy: An Interview with Nina Lorez Collins

By Yasmina Price

Yasmina Price interviewed author Nina Lorez Collins, daughter of writer and filmmaker, Kathleen Collins, about her mother’s legacy, the dynamics of their relationship, and the process of preserving and archiving her artistic output.

Nina Lorez Collins has pursued various paths of nurturing cultural production and facilitating connections. Previously a literary scout, book agent, and creator of an online community for women over 40, now having turned that group into the digital platform, The Woolfer, and taking on the role of Board Chair for The Brooklyn Public Library, Collins has also been the caretaker of her mother’s, the extraordinary writer and filmmaker Kathleen Collins, legacy.

Collins, a mother of four, is a graduate of Barnard College and obtained a Masters in Narrative Medicine from Columbia University. She published her first book, What Would Virginia Woolf Do?: And Other Questions I Ask Myself as I Attempt to Age Without Apology in 2018 and for over a decade was working on a memoir about her mother. The memoir proved to be more about entering into a thoughtful, ongoing process of coming to terms with herself, the way her mother shaped her and finding a form of personal peace, then producing a finished product.

With steely grace, Collins has navigated the complexities of posthumously reckoning with her mother as a full person, the dynamics of their relationship, the abruptness of losing her to a cancer she had kept secret for years, all while maintaining a dedication to championing Kathleen Collins’s artistic output. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Collins’s decision to take on the restoration of Losing Ground (1982) was an important gain for cinema in general, and certainly for Black Independent Film and Black Women’s Cinema in particular.

Neither Losing Ground, shown for the first time in 2015 during the “Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York 1968–1986” co-curated by Michelle Materre and Jake Perlin at the Lincoln Center Film Society nor her preceding The Cruz Brothers and Mrs. Malloy (1980) had a theatrical release in the filmmaker’s lifetime. Collins also compiled together some of her mother’s short stories into Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? (2016) and mixture of more short stories, plays, screenplays and diary fragments in Notes From a Black Woman’s Diary (2019).

Collins has undertaken this work of care and preservation with generosity and the willingness to offer it as a shared task, to be passed through many hands.

Yasmina Price (YP): Could we begin with speaking about the memoir you’re writing about your mother?

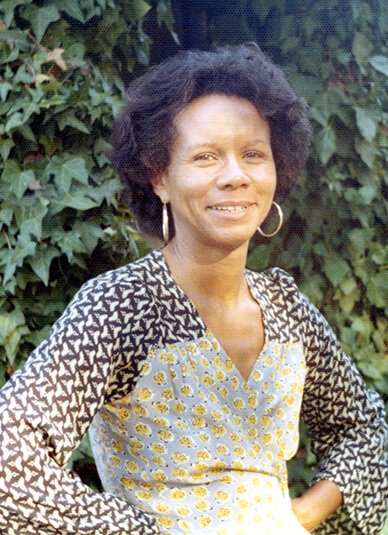

Photo of Nina Lorez Collins. Photo retrieved from passerbymagazine.com.

Nina Lorez Collins (NLC): I started this memoir when I was 30. About 15 years ago was when I started unearthing her work. I spent a couple years post-divorce very depressed, going through a really difficult time in my life that brought a lot of separation issues, anxiety, and abandonment to the fore. I was really trying to understand my own emotional problems and I went to look in this trunk of my mother’s work to figure it out. I read everything and I thought, well, I'll write a memoir. I had never thought about writing until then or that I had a story I wanted to tell, even though I was in publishing.

I sold my agency at 37 and I wanted to try and write this memoir as an intellectual challenge for myself, and to help myself emotionally. I wrote a draft of it. I have a really good friend who's an agent, she became my agent, we submitted it, and it didn't sell. We tried again–it still didn’t sell. I was super discouraged, of course, and put it away. I applied to graduate school, spent another 10 years kind of going back and forth with it. During that time, I got Losing Ground (1982) remastered, and then had Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? (2016) and Notes From a Black Woman’s Diary (2019) published.

I started this Facebook group called “What Would Virginia Woolf Do” and I ended up writing a book for that. At this point, I was feeling a lot better and after that book came out in 2018, I decided to go back and try and finish the memoir. I spent all of 2019 working on it, finishing it to my satisfaction, and it was quite different by that point. Then I went out and tried to sell it again and it still didn't sell.

I have to say the book is super personal and quite dark. At the time, I was in the middle of relaunching my company, so I gave it a few more passes and then I kind of decided I'll go back to it again. What happened a few months later was that I realized that I had written what I wanted to write and I was done with it. I've actually kind of walked away from it, and I don't think that I'll ever go back.

I sometimes wonder: Is there a place in the world for it? Or is there something else that I should be doing with it? I think people really wanted me to write a more conventional biography of her, which I didn't really want to do. I think the best parts were what I wrote about my childhood. I was really trying to look at how I became the mother I am, the woman I am, and what kind of woman and mother she was.

Nina Lorez Collins as a child with her mother, Kathleen Collins. Photo courtesy of Nina Lorez Collins.

I'm now so happy and at peace in my life. It's actually kind of bizarre–I never in a million years expected that I'd be okay. I was doing a lot of therapy, I was writing the memoir, and I was also doing everything to put her work out there. It helped me to eventually forgive her. I think the central mystery I was trying to figure out in writing, or at least when I started it was: Why did she keep her illness a secret? And why was she so emotionally removed from us? Those are the things that I was really trying to understand. My mother was always in her head, it’s fair to say self-absorbed, but also in her way a great mother and of course, really brilliant. I really felt loved by her but I think she was really an artist and I think real artists are impossible.

She was always in her head, in her room, in her writing, and she couldn't do things; it was just funny. I remember once helping her wrap up some hard boiled eggs for my brother's lunch. She couldn't figure out how to wrap the hard boiled eggs. There are many ways in which she was very competent but also just not.

That’s another thing I think I've realized over time: I often miss my two grandmothers more because they were a little bit more emotionally part of my daily life. They both died when I was in my forties, so I also had them much longer. I had my grandmother's for an extra 20 years. I miss them in a way that's different from how I miss my mother.

YP: This makes me think of how your website notes you have an interest in thinking through loss, separation, and end of life. Would you speak a little about that?

NLC: We're constantly dealing with loss. The question is how we can be whole enough to manage what we need within ourselves and not just act out against everyone around us? How do we deal with our own death? Am I going to be able to be contained enough to handle my death thoughtfully and gracefully? Some people hate the term “aging gracefully,” but I don't mind it. I feel like I want to be me. Being able to have grace is also a sign of being healthy and having boundaries.

YP: Is this related to the women’s groups you’ve founded and been running in various capacities? I was also wondering if there’s maybe some dimension of political education to them and if that’s something you got from your mother? What sort of sense did you have of her as political person and how did it influence you?

NLC: She grew up in this kind of conservative home and raised me in not a conservative home. I think she was expected to become a teacher like her sister and dad were. She went to Skidmore College and she was politicized there. I would say it was mostly from 1958 to 1965–let’s say from ages 17 to 25/26–that she probably considered herself really political. Then she started editing films for PBS, developing her film career, and writing plays and short stories. While there is political stuff for sure, the personal is political in all of her work.

She also never voted as far as I knew as a kid and she did not talk to me about voting. She took us to cultural things all the time but I don’t remember her actually really talking about politics. Another thing that I grappled with was really trying to understand how little she talked to us about race.

Images of writer and filmmaker, Kathleen Collins. Sources: Smithsonian African American Film Festival, The Story Bar, and Kathleen Collins’ Website.

YP: I would never have guessed that she didn’t! I suppose this does somewhat align with how race manifests in her work—always present but not so much directly addressed as metabolized, through the ways she excavates interior spaces that generates particular interpersonal dynamics.

NLC: I think that's true in her writing and her films. I'm sure you've watched the Howard interview? Well, when you watch the Howard interview, it's super interesting because that one is about race! It has a very strong point of view that I really love. She speaks about her refusal to be mythologized. I think this was reflected a little bit in how she raised us–she really didn’t want us to feel pathologized by race. She didn’t want her characters to feel that way either.

YP: Most people who are now familiar with your mother’s work think of her films, but she was a prolific writer in many forms, including plays. I believe there’s been some recent resurfacing of her work in the theatre context?

NLC: Yes, Eisa Davis produced a play in New York and there was one in Oakland, California at the Oakland Theater Project. It was super cool, actually—even speaking to you—just seeing especially the way young Black women are interpreting her work. I couldn’t be happier. It's been so interesting as time goes on to see how it’s received, and how younger generations of people are processing it. It made me feel like she can be really important to understanding different layers of identity for young Black women today and I just feel really lucky about it and proud.

I'm thrilled lots of people went to see Losing Ground and there’s also something about how it’s been more people over time–maybe post-George Floyd. It’s something about the way Black women or Black women artists are being encouraged in the artistic space more than I’ve think we've seen before, which is kind of weird and also cool, obviously.

Video of Kathleen Collins speaking at Howard University in 1984. Source: Kathleen Collins Website/Milestone Channel.

YP: Yes, it’s a bit of a double-edged sword wherein there’s the component of a pacifying gesture on the part of institutions, and the state, in a way that doesn’t remotely signal any substantial structural changes.

NLC: It's totally weird! And has the world changed? Well, it's changing in some ways. I spent 20 years in book publishing, there were no Black people in publishing and it's great they're hiring Black people now.

YP: How did you end up pursuing a career in publishing? I could imagine you might have grown up surrounded by books.

“That was probably the absolute best gift she gave me: incredibly powerful, and with incredible strength. Even though she was definitely somewhat depressed a fair amount of the time, she was just a powerhouse. She had this really strong laugh. She was really funny. She was brave. I think those things informed who I could be.”

NLC: I mostly grew up surrounded by books! Although in high school, I thought I was going to become a lawyer. Then I left for Vienna–I speak German–maybe the year before my mother died, and she said, “You're not going to be a lawyer.” I had gone to Vienna as a teenager and fallen in love. Then when my mom died, I came home from Vienna. When I got back, I was working for this hedge fund guy as an administrative assistant. Anyway, I met someone who needed someone who spoke German and I fell into scouting for European publishers. I have always been a huge reader. My mom was a huge reader; books were a big part of our lives. I kind of fell into publishing in a way that made sense.

I think I really purposely went into the business side of it. I didn't want to be an editor—I was a scout and I was an agent. I had seen my mother struggle so much on the creative side with film and not having enough money to do it. I wasn't interested in being in the creative side of things for a long time. I didn't think that I had it in me. I think it's funny: I was saying to someone yesterday that sometimes I look back and I wish I'd had a more conventional life. Clearly, I didn't really want that, or I could have created it. I do think I was rebelling a little bit against the mayhem of my childhood but I ended up still kind of doing things that are off the beaten path.

You look at women and how mothers are models for what we become. My mother really did make me feel like I could do anything. That was probably the absolute best gift she gave me: she was incredibly powerful and had incredible strength. Even though she was definitely somewhat depressed a fair amount of the time, she was just a powerhouse. She had this really strong laugh. She was really funny. She was brave. I think those things informed who I could be.

YP: That really is so moving! Truly, what a gift. And when you were in Vienna you and your mother wrote letters to each other, is that right?

NLC: Yes! I still have them all. When I was growing up, she would write me letters. When we had a fight, I would come home after school, and I would find a type-written letter on my pillow. When I was a teenager we had all these beautiful, incredible letters. A couple of them are in Notes from a Black Woman's Diary. Kind of inappropriate also, sometimes talking to me as if I was more of an adult than I was but she would always write to me. When I was around 15, I started going to Vienna a lot over the next three years, and we wrote a lot of letters back and forth to each other. Then that final year–I left in December 1987–for a year abroad. A week after I left, she went into the hospital but she wrote to me and said she had some sort of spinal injury.

She didn't say it was cancer, and we spent that whole year writing back and forth in those letters. The letters are great. They're really chatty and funny. They're about neighbors, her work, her new marriage, and my brother. She also talks about not being able to give us as much love as she wished she had when we were younger and about having been in her own pain too much. Then after she died, I found her journals. It was really crazy because I could see on January 8, there'd be a letter to me and then in her journal, on the same date, she's talking about her fear of death, the pain in her body, and she's a full on cancer patient but she didn't share any of that with me at all!

Stills from Kathleen Collins’ 1982 Losing Ground, one of the first feature films directed by an African American woman. Stills retrieved from kathleencollins.org.

YP: That must have been incredibly difficult and so much for you to negotiate, but I imagine it’s maybe all the more precious to have those written traces of your relationship. I wonder if having these various components of her archive—the letters, old papers, the films—has presented its own set of difficulties? Because what might seem like the archive of an artist to fans of her work is also just your mother’s stuff, objects with a certain sentimental value, perhaps?

NLC: It's the weirdest thing with a mother or someone you see every day and the difficulty of the transition and the very palpable loss. Now it's a little like, I don't need her things because I remember her things. I think in the beginning, you reach for it because you feel like it's all you have left or at least it's something to hold. But the person is gone and eventually you just learn that stuff just doesn't matter. I didn't even know I was living her archive, her actual archive. I did carry it around for 20 years or a little bit more than that.

Eventually, it felt a little bit like an albatross. I was worried if I get hit by a bus, would the kids know what to do with this? I started to feel a responsibility toward it. It seemed like a perfect solution to give it to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and then everyone would have access. It's safe and I feel good about that.

Sometimes, I realize I don't have something I thought I had kept and I'm like, well, it's numbered. If I really need to see it, I can go there. Doing all this with her work–with Losing Ground–was sort of a weird experience. I really thought I was just doing it for my family and then it became so successful. Then I did the books. I feel like I've done a lot and it's all really good. Now, I don't really have to do anymore. There was some interest in doing a couple books with her plays and screenplays. I think that would be awesome. However, I've decided I don't really have the time or the wherewithal to do it. I’m happy to pass on that task.

For more information about Nina Lorez Collins, please visit ninalorezcollins.org.

For more information about Kathleen Collins, please visit kathleencollins.org

About the author: Yasmina Price is a writer, researcher, and PhD student in the Departments of African American Studies and Film & Media Studies at Yale University. She focuses on anti-colonial African cinema and the work of visual artists across the Black diaspora, with a particular interest in the experimental work of women filmmakers. She has interviewed filmmakers and participated in panels on black film and revolutionary cultural production organized by The Maysles Documentary Center, International Documentary Association, New York Film Festival and more. Recent writing has appeared in The Current (Criterion), The New Inquiry, The New York Review of Books, the Metrograph Journal, Vulture, Hyperallergic and MUBI. You can follow her on Twitter @jasminprix.