Celebrating the Enduring Legacy of Black Bookstores: An Interview with Katie Mitchell, Author of Prose to the People

Photo of author and publisher Katie Mitchell. Photo by Scott Dinerman. Photo courtesy of Penguin Random House.

By Karla Méndez

In honor of the publication of her book, Prose to the People: A Celebration of Black Bookstores, writer and bookseller, Katie Mitchell discusses the importance of Black bookstores, their role as sites of liberation, and community building through books.

At the end of 2022, it was reported by the American Booksellers Association that there were 2,599 independent bookstores in the United States. According to WordsRated, 149 of these are Black owned. These bookstores follow in a long tradition as spaces to convene, engage in conversation, learn about history, and build community through reading. Bookstores, much like libraries, become a third place, coined by Ray Oldenburg as a place outside the home and workplace that people voluntarily go to to converse and connect with their community. For Black communities, the bookstore has been the site of abolitionist activity, like the first Black Bookstore in the United States, D. Ruggles Books. It has been a connection to the outside world for incarcerated folks through programs at stores like the Hue-Man Experience, Radical Hood Library, and The Black Book, which have provided books to jailed individuals.

Black bookstores are a testament to the resiliency of Black Americans and our commitment to breaking free of our physical and spiritual chains. We’ve always been acutely aware of the importance of literacy as throughout the history of the United States there have been laws and systems put in place to keep Black Americans from learning to read as it would be dangerous and make them difficult to control. Anti-literacy laws were passed between 1740 and 1867 in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, amongst others. Despite the threat of fines, imprisonment, and violence, Black Americans, both freed and enslaved, continued to find ways to read. The opening of David Ruggles bookstore introduced a new frontier in the struggle for liberation through literacy, which continues today.

Black bookstores hold our history. They teach us about those who came before us and allow us to write our stories for those who will come after. As Glenderlyn Johnson, owner of Black Books Plus, said, “It’s important to tell the story, to teach the history” (Footnote 1).

Please note: This interview has been edited for readability.

Karla Méndez: What inspired you to curate Prose to the People? It’s done in such a beautiful way that not only focuses on the bookstores, but also the people who frequented them and their history with them.

Katie Mitchell: I wanted Prose to feel like a Black bookstore. When you go into a bookstore you're not just hearing from one person; there are multiple authors, different genres. There are essays, poetry, interviews about vibrant, beautiful places. That’s why I wanted to have it be full of pictures and ephemera because the visual history tells so much about Black history in general. So many people have different relationships with bookstores, and I wanted to capture that. The more voices, the better the history is told.

Front cover of Prose to the People. Photo courtesy of Penguin Random House.

Karla: You had the honor of having Nikki Giovanni write the foreword for your book. As someone whose work has documented Black American history in poetry and essays, what was the experience like having her introduce your book?

Katie: I decided I wanted to ask Nikki Giovanni [to write the foreword] when I was recording the book. I knew it was an audacious thing to ask, but when I was talking to people who had bookstores between the 60s and early 2000s, everyone had a Nikki Giovanni story. And they were all very positive. I thought it was only right that she had the first word in the first book about Black bookstores. When I reached out to her, I let her know what her work has meant to me at different points in my life. She was so gracious. She’s a good example of what it means to be an elder. And with her passing, I’m grateful that she lived and that she’s not in pain anymore, but I think she’s also an example of being a good ancestor. She set Prose up in a way that it could go further places with her name on the cover and her words in the book. I’m really honored that she said yes.

Karla: What inspired you to become a bookstore owner?

Katie: It was my mom. She raised us on Black books. I was fresh out of college and my friends were coming over. I had a very basic bookshelf with Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, James Baldwin, stuff like that. They were like “Oh my god! Who is this person?” And these were college educated people and I was surprised they didn’t know Toni Morrison; but I also went to an engineering school. I was telling my mom about that and she suggested we start a bookstore to get people back into the love of reading. I feel like in elementary school, everybody was reading but then it declined. It became a chore as we got older. Seeing that people need to know more about these Black authors that I view as important, but they hadn’t heard of was the inspiration.

Karla: Can you recall your first experience visiting a bookstore, specifically a Black owned bookstore?

Katie: I’m from Atlanta and there’s this mall on the Southside called South Lake where there was a bookstore for the longest time called Nubian Bookstore. It’s now across the street. I really liked going there. It used to be right next to a toy store, and I would always opt to go in there [the bookstore]. That’s my first memory of a Black bookstore. In adulthood, I spent a lot of time at For Keeps, which is an antiquarian bookstore on Auburn Avenue, a very famous Black street in Atlanta.

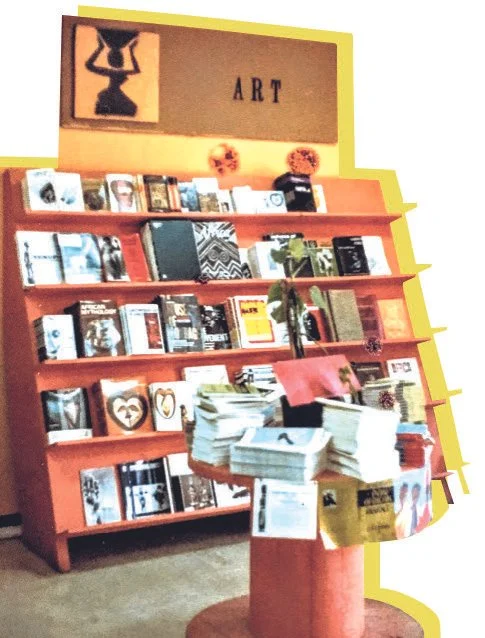

Drum and spear press art shelves. Courtesy of Jennifer Lawson/Penguin Random House.

Karla: Do you remember what were some of the first bookstores you interacted with at either bookstore?

Katie: I know For Keeps–they have a crazy selection. They have books that were originally printed during the Harlem Renaissance. They have them out so anybody can touch them, which I think is important because being someone who has done research and been in the archives, you must have an ID, you have to have an appointment. You have to pass all these different checks to make sure you’re worthy of looking at this material, but she just has it out. I remember looking for books that were printed by Drum and Spear Press, a bookstore in Washington, D.C. in the 60s that also had a press. They’re so rare and expensive. Of course, she did have some in the store. With Nubian Bookstore, I remember being obsessed with books about segregation in school.

Karla: How do you see Black owned bookstores as a type of living archive?

Katie: I think that’s the cool thing about Prose is that I picked what bookstores were going to be in it and from the decision to the publication, some have already closed. It’s a snapshot of this very particular moment in time in which these bookstores existed. Of course, it’s sad when a Black bookstore closes. The community loses something, but I think that’s what it means to be an institution. One Black bookstore closing does not end the institution. There’s going to be one coming after it. I think with Prose now, for people aspiring to open a bookstore in the future, they can go and read about different bookstores and see what they did well and what they did wrong. They can learn from their mistakes and keep the institution going that way. While I was in the archive, I found these different connections that aren’t out there for people to know. It was like a family tree of Black bookstores and the way they’re connected. It was this great lineage that wasn't clear to me until I went into the archives.

“It was like a family tree of Black bookstores and the way they’re connected. It was this great lineage that wasn’t clear to me until I went into the archives.”

Karla: In the book, Garrett Felber writes about the ability of bookstores to contort and reshape themselves over time, space, and place and they represent open possibilities for creating community spaces and political education that are beyond state capture (Footnote 2). In the current political landscape of our country, what do you see as the role of Black owned bookstores?

Katie: Black bookstores are in this very long tradition of being at the vanguard of social change. If you go all the way back to the first known Black bookstore, the owner David Ruggles was an abolitionist. He helped free Frederick Douglass and countless other fugitive slaves. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that he was also a bookstore owner. He was writing anti-slavery and abolitionist literature, printing it in his shop, and then selling it. He faced the consequences of that. He was jailed and his store was set on fire. With Black bookstores today, he sets the tone of them being the site of liberation in the United States. We must continue that. We see it throughout Prose. We see Drum and Spear in the 1960s going up against the FBI. You see in Garrett’s essay about Martin Sostre and the Afro-Asian bookshop being framed. His real crime was that he was selling books and making Black people feel empowered through those books. It’s important to know that history and know that we’ve been here before. We’ve faced oppression in this sense and carry the torch forward.

Sometimes I hear people say, “Oh, a book ban? Let me make sure that’s not in my house.” I tell them they’re not going to search your house. It’s not illegal [to own the book]. The important thing is to not comply with these book bans and to make the books accessible to people. If they’re banning a book, there’s probably something in it that you need to know and the people who don’t want a wholesome life for Black people in the United States, they’re doing this for a reason. It’s important to vocalize that and share with people, not just the people that are always in the bookstores. Everybody needs to know this because it’s going to impact them eventually.

Afro-Asian Bookshop-in-Exile replica, “Sostre at 100,” Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, photo by Zachary Dean Norman. Photo courtesy of Penguin Random House.

Karla: Black owned bookstores have historically been sites for social justice movements and liberation, but with the prevalence of the internet and platforms like Amazon, how do you think that might impact Black owned bookstores and their ability to keep their doors open?

Katie: That’s Amazon’s whole goal. They undercut these bookstores and sell books at a loss. The indies can’t compete with that, and they go out of business. Even before Amazon, the big box stores were doing the same thing. It’s very intentional, but I think people have become wiser to it. Independent bookstore day was this past weekend, and I saw the swell of support for that. You must realize what these large corporations like Amazon are doing and then make your informed decision based on that. Is it more important to live in a world where your books are 90% off or is it more important to live in a world where you have access to books through your independent bookseller who actually cares about the community?

Karla: How have you discovered your language through reading and bookstores?

Katie: I’ve learned so much while writing this book. Writing this book it’s like from Wednesday to Wednesday, I’m a whole new person because of the people I’ve talked to and the experiences I’ve had. I can see my mind growing so much throughout the pages and I hope that helps others too. How do we move in the face of harassment and oppression? How do we hold each other as a community? How do we make sure we’re bringing along people who may otherwise be left behind? I love the bookstores who say we’re not focusing so much on the intellectuals and the academics because they’ve already got it. We’re focusing on the people who only read tabloids and we’re bringing them along on this reading journey. It’s helped me find a new mindset.

Karla: In what ways do you consider reading to be a political act?

Eloise Greefield looking at Bubbles on the shelves of Drum and Spear. Courtesy of Monica Greefield/Penguin Random House.

Katie: From the first time we stepped on these shores reading was a no-no. No reading was allowed on the plantation. There’s that quote from Frederick Douglass about his master finding out someone was teaching him how to read, and he said if he learns how to read, he can’t be a slave anymore. And I think that sentiment is still true and that’s why these book bans disproportionately impact Black authors, and books that have Black characters and speak about the Black experience. It’s always been political. It is still political. I think it’ll be great when a day comes where people aren’t trying to dictate what Black people read or put out. But from what I’ve seen, the whole project has been under attack, from the reading to the writing, to the publishing, to the archiving. If we see ourselves as political people, we have to keep reading because reading changes our minds and then we’re able to change society. I’ve seen that time and time again. The best movements have well-read people who know what’s going on and they can communicate that to others.

Karla: Una Mulzac was haunted by the fact that many vital books published during the 1960s and 70s were no longer in print and difficult to acquire. Have you encountered a book that has been or is currently out of print that has been influential to your practice?

Katie: The one I’m thinking of was recently put back into print because Black Thought staged a Broadway play about it. It’s called “Black No More” [by George Schuyler]. I liked that book because it’s very old,but it felt contemporary and it reminded me of the beauty standards of today. It also had the political and social commentary of Black people who are profiting off Black people not feeling good about themselves. I think that just changed me in a way of thinking about what I am doing that’s contributing to white supremacy as a Black person. Am I packaging things that are supposed to feel like Black empowerment, but are really playing on people’s insecurities? Since I found that book, I’ve picked it up every year. The Black Book came back into print in the 2020s. That’s a book that if you look at it, you can see the influence that it had on Prose to the People with the collage, scrapbook type of feel.

Karla: With the ongoing book bans, how do we keep current books from meeting that same fate of going out of print?

Katie: I think that is a question for the booksellers. Sometimes we can get fixated on the new releases and not look at the back list or vintage titles. I love a bookstore that’s well curated and that I can tell the people in the bookstore read the books and they’re able to sell it in a way that makes it appealing to someone who has never heard of the book. As a bookseller, there are books that I find just off the strength of me being a reader and I can see once I start posting and talking about it, other bookstores picking it up. It is a communal practice of talking about these books, reading them so you’re able to speak about them in an intelligent way, and then sharing them.

“My body may be imprisoned, but my mind is free.”

Karla: Many of the bookstore owners in the book had programs in which they would send incarcerated folks’ books. Can you talk a little about why you think this is an important practice?

Katie: Even speaking of book bans, there’s a way that what happens in prisons mirrors what will eventually happen outside of those walls. If we’re feeling the book bans, their ability to read has been shut down even more. The bookstores that focus on that, I admire them so much because it’s a statement saying we care about these people. They’re trying to disappear them from our society, but we care about the life of their mind, we care about informing them about what’s going on. It’s important because if the whole point of prison is rehabilitation, why shouldn’t they be able to read? We see what happened with Malcolm X who was in a more experimental prison, and they were letting him read these books and we see what he was able to do with his life. I think that the bookstores that focus on folks who are incarcerated and making sure that they have access to that material is crucial. If you see how books change us as free people, imagine how books can change [incarcerated folk].

Karla: What are some of the books that have been foundational to your life?

Katie: I remember Their Eyes Were Watching God [by Zora Neale Hurston] was my first favorite book. I also really loved Homegoing by Yaa [Gyasi]. They are books that make me feel like I want to be a writer now. Those are two that have been super foundational to me. The Black Book as far as being an editor and curating a cohesive story was cool for me to see. I love Z.Z. Packer. She has a collection of short stories, Drinking Coffee Elsewhere. I haven’t written fiction before but she’s a big inspiration for my eventual fiction practice.

Footnotes

[Mitchell, Katie, Prose to the People: A Celebration of Black Bookstores (New York, Clarkson Potter, 2025), 47.

Felber, Garrett, “Nothing Disappears in This World,” in Prose to the People: A Celebration of Black Bookstores, ed. Katie Mitchell (New York, Clarkson Potter, 2025), 37.

About the author: Karla Méndez is an arts and culture writer whose work examines the histories of Black and Latin American women and their representations within visual art, literature, poetry, and performance. She is interested in how women put forth representations of themselves that are accurately representative of their expansiveness and how they use these avenues to engage with topics of identity, gender, race, and the female body. Ultimately, her work seeks to explore and reinstate forgotten and ignored histories as a site of care for ourselves and our communities.

She is the lead columnist of Black Feminist Histories and Social Movements, a column for the advocacy organization Black Women Radicals. She is a contributor for the Boston Art Review and Elephant Magazine and her work has appeared in the Brown Art Review and Ampersand: An American Studies Journal.